Macintosh

The Macintosh (pronounced /ˈmæk.ɪn.tɒʃ/ MAK-in-tosh),[1] or Mac, is a series of several lines of personal computers designed, developed, and marketed by Apple Inc. The first Macintosh was introduced on January 24, 1984; it was the first commercially successful personal computer to feature a mouse and a graphical user interface rather than a command-line interface.[2] The company continued to have success through the second half of the 1980s, only to see it dissipate in the 1990s as the personal computer market shifted towards IBM PC compatible machines running MS-DOS and Microsoft Windows.[3]

Apple consolidated its multiple consumer-level desktop models years later into the 1998 iMac all-in-one. This proved to be a sales success and saw the Macintosh brand revitalized, albeit not to the market share level it once had. Current Mac systems are mainly targeted at the home, education, and creative professional markets. They are: the aforementioned (though upgraded and modified in various ways) iMac and the entry-level Mac mini desktop models, the workstation-level Mac Pro tower, the MacBook, MacBook Air and MacBook Pro laptops, and the Xserve server.

Production of the Mac is based on a vertical integration model in that Apple facilitates all aspects of its hardware and creates its own operating system that is pre-installed on all Mac computers. This is in contrast to most IBM PC compatibles, where multiple sellers create hardware intended to run another company's operating software. Apple exclusively produces Mac hardware, choosing internal systems, designs, and prices. Apple does use third party components, however. Current Mac CPUs use Intel's x86 architecture; the earliest models (1984–1994) used Motorola's 68k and models from 1994–2006 used the AIM alliance's PowerPC. Apple also develops the operating system for the Mac, currently Mac OS X version 10.6 "Snow Leopard". The modern Mac, like other personal computers, is capable of running alternative operating systems such as Linux, FreeBSD, and, in the case of Intel-based Macs, Microsoft Windows. However, Apple does not license Mac OS X for use on non-Apple computers.

Contents |

History

1979 to 1984: Development

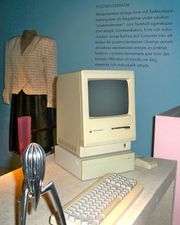

Left to right: George Crow, Joanna Hoffman, Burrell Smith, Andy Hertzfeld, a Macintosh, Bill Atkinson, Jerry Manock.

The Macintosh project started in the late 1970s with Jef Raskin, an Apple employee, who envisioned an easy-to-use, low-cost computer for the average consumer. He wanted to name the computer after his favorite type of apple, the McIntosh,[4] but the name had to be changed for legal reasons as it was too close, phonetically, to that of the McIntosh audio equipment manufacturer. Steve Jobs requested a release of the name so that Apple could use it but this was denied forcing Apple to eventually buy the rights to use the name.[5] Raskin was authorized to start hiring for the project in September 1979,[6] and he began to look for an engineer who could put together a prototype. Bill Atkinson, a member of Apple's Lisa team (which was developing a similar but higher-end computer), introduced him to Burrell Smith, a service technician who had been hired earlier that year. Over the years, Raskin assembled a large development team that designed and built the original Macintosh hardware and software; besides Raskin, Atkinson and Smith, the team included George Crow,[7] Chris Espinosa, Joanna Hoffman, Bruce Horn, Susan Kare, Andy Hertzfeld, Guy Kawasaki, Daniel Kottke,[8] and Jerry Manock.[9][10]

Smith’s first Macintosh board was built to Raskin’s design specifications: it had 64 kilobytes (KB) of RAM, used the Motorola 6809E microprocessor, and was capable of supporting a 256×256 pixel black-and-white bitmap display. Bud Tribble, a Macintosh programmer, was interested in running the Lisa’s graphical programs on the Macintosh, and asked Smith whether he could incorporate the Lisa’s Motorola 68000 microprocessor into the Mac while still keeping the production cost down. By December 1980, Smith had succeeded in designing a board that not only used the 68000, but bumped its speed from 5 to 8 megahertz (MHz); this board also had the capacity to support a 384×256 pixel display. Smith’s design used fewer RAM chips than the Lisa, which made production of the board significantly more cost-efficient. The final Mac design was self-contained and had the complete QuickDraw picture language and interpreter in 64 KB of ROM – far more than most other computers; it had 128 KB of RAM, in the form of sixteen 64 kilobit (Kb) RAM chips soldered to the logicboard. Though there were no memory slots, its RAM was expandable to 512 KB by means of soldering sixteen chip sockets to accept 256 Kb RAM chips in place of the factory-installed chips. The final product's screen was a 9-inch, 512x342 pixel monochrome display, exceeding the prototypes.[11]

The design caught the attention of Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple. Realizing that the Macintosh was more marketable than the Lisa, he began to focus his attention on the project. Raskin finally left the Macintosh project in 1981 over a personality conflict with Jobs, and team member Andy Hertzfeld said that the final Macintosh design is closer to Jobs’ ideas than Raskin’s.[6] After hearing of the pioneering GUI technology being developed at Xerox PARC, Jobs had negotiated a visit to see the Xerox Alto computer and Smalltalk development tools in exchange for Apple stock options. The Lisa and Macintosh user interfaces were partially influenced by technology seen at Xerox PARC and were combined with the Macintosh group's own ideas.[12] Jobs also commissioned industrial designer Hartmut Esslinger to work on the Macintosh line, resulting in the "Snow White" design language; although it came too late for the earliest Macs, it was implemented in most other mid- to late-1980s Apple computers.[13] However, Jobs’ leadership at the Macintosh project did not last; after an internal power struggle with new CEO John Sculley, Jobs resigned from Apple in 1985,[14] went on to found NeXT, another computer company,[15] and did not return until 1997 when Apple acquired NeXT.[16]

1984: Introduction

The Macintosh 128k was announced to the press in October 1983, followed by an 18-page brochure included with various magazines in December.[17] The Macintosh was introduced by the now famous US$1.5 million Ridley Scott television commercial, "1984".[18] The commercial most notably aired during the third quarter of Super Bowl XVIII on 22 January 1984 and is now considered a "watershed event"[19] and a "masterpiece."[20] "1984" used an unnamed heroine to represent the coming of the Macintosh (indicated by a Picasso-style picture of Apple’s Macintosh computer on her white tank top) as a means of saving humanity from the "conformity" of IBM's attempts to dominate the computer industry. The ad alludes to George Orwell's novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which described a dystopian future ruled by a televised "Big Brother."[21][22]

Two days after the 1984 ad aired, the Macintosh went on sale. It came bundled with two applications designed to show off its interface: MacWrite and MacPaint. It was first demonstrated by Steve Jobs in the first of his famous Mac Keynote speeches, and though the Mac garnered an immediate, enthusiastic following, some labeled it a mere "toy."[23] Because the operating system was designed largely around the GUI, existing text-mode and command-driven applications had to be redesigned and the programming code rewritten. This was a time consuming task that many software developers chose not to undertake, and could be regarded as a reason for an initial lack of software for the new system. In April 1984 Microsoft's MultiPlan migrated over from MS-DOS, with Microsoft Word following in January 1985.[24] In 1985, Lotus Software introduced Lotus Jazz for the Macintosh platform after the success of Lotus 1-2-3 for the IBM PC, although it was largely a flop.[25] Apple introduced Macintosh Office the same year with the lemmings ad. Infamous for insulting its own potential customers, it was not successful.[26]

For a special post-election edition of Newsweek in November 1984, Apple spent more than US$2.5 million to buy all 39 of the advertising pages in the issue.[27] Apple also ran a “Test Drive a Macintosh” promotion, in which potential buyers with a credit card could take home a Macintosh for 24 hours and return it to a dealer afterwards. While 200,000 people participated, dealers disliked the promotion, the supply of computers was insufficient for demand, and many were returned in such a bad shape that they could no longer be sold. This marketing campaign caused CEO John Sculley to raise the price from US$1,995 to US$2,495 (adjusting for inflation, about $5,200 in 2010).[26][28]

1985 to 1989: Desktop publishing era

In 1985, the combination of the Mac, Apple’s LaserWriter printer, and Mac-specific software like Boston Software’s MacPublisher and Aldus PageMaker enabled users to design, preview, and print page layouts complete with text and graphics—an activity to become known as desktop publishing. Initially, desktop publishing was unique to the Macintosh, but eventually became available for Commodore 64 (GEOS) and IBM PC users as well.[29] Later, applications such as Macromedia FreeHand, QuarkXPress, Adobe Photoshop, and Adobe Illustrator strengthened the Mac’s position as a graphics computer and helped to expand the emerging desktop publishing market.

The limitations of the first Mac soon became clear: it had very little memory, even compared with other personal computers in 1984, and could not be expanded easily; and it lacked a hard disk drive or the means to attach one easily. In October 1985, Apple increased the Mac’s memory to 512 KB, but it was inconvenient and difficult to expand the memory of a 128 KB Mac.[30] In an attempt to improve connectivity, Apple released the Macintosh Plus on January 10, 1986 for US$2,600. It offered one megabyte of RAM, expandable to four, and a then-revolutionary SCSI parallel interface, allowing up to seven peripherals—such as hard drives and scanners—to be attached to the machine. Its floppy drive was increased to an 800 KB capacity. The Mac Plus was an immediate success and remained in production, unchanged, until October 15, 1990; on sale for just over four years and ten months, it was the longest-lived Macintosh in Apple's history.[31]

Updated Motorola CPUs made a faster machine possible, and in 1987 Apple took advantage of the new Motorola technology and introduced the Macintosh II, which used a 16 MHz Motorola 68020 processor.[32] The primary improvement in the Macintosh II was Color QuickDraw in ROM, a color version of the graphics language which was the heart of the machine. Among the many innovations in Color QuickDraw were an ability to handle any display size, any color depth, and multiple monitors. Other issues remained, particularly the low processor speed and limited graphics ability, which had hobbled the Mac’s ability to make inroads into the business computing market.

The Macintosh II marked the start of a new direction for the Macintosh, as now, for the first time, it had an open architecture, with several expansion slots, support for color graphics, and a modular break-out design similar to that of the IBM PC and inspired by Apple’s other line, the expandable Apple II series. It had an internal hard drive and a power supply with a fan, which was initially fairly loud.[33] One third-party developer sold a device to regulate fan speed based on a heat sensor, but it voided the warranty.[34] Later Macintosh computers had quieter power supplies and hard drives.

In September 1986 Apple introduced the Macintosh Programmer's Workshop, or MPW that allowed software developers to create software for Macintosh on Macintosh, rather than cross-developing from a Lisa. In August 1987 Apple unveiled HyperCard, and introduced MultiFinder, which added cooperative multitasking to the Macintosh. In the Fall Apple bundled both with every Macintosh.

The Macintosh SE was released at the same time as the Macintosh II, as the first compact Mac with a 20 MB internal hard drive and one expansion slot.[35] The SE also updated Jerry Manock and Terry Oyama's original design and shared the Macintosh II's Snow White design language, as well as the new Apple Desktop Bus (ADB) mouse and keyboard that had first appeared on the Apple IIGS some months earlier.

In 1987, Apple spun off its software business as Claris. It was given the code and rights to several applications that had been written within Apple, notably MacWrite, MacPaint, and MacProject. In the late 1980s, Claris released a number of revamped software titles; the result was the “Pro” series, including MacPaint Pro, MacDraw Pro, MacWrite Pro, and FileMaker Pro. To provide a complete office suite, Claris purchased the rights to the Informix Wingz spreadsheet on the Mac, renaming it Claris Resolve, and added the new presentation software Claris Impact. By the early 1990s, Claris applications were shipping with the majority of consumer-level Macintoshes and were extremely popular. In 1991, Claris released ClarisWorks, which soon became their second best-selling application. When Claris was reincorporated back into Apple in 1998, ClarisWorks was renamed AppleWorks beginning with version 5.0.[36]

In 1988, Apple sued Microsoft and Hewlett-Packard on the grounds that they infringed Apple’s copyrighted GUI, citing (among other things) the use of rectangular, overlapping, and resizable windows. After four years, the case was decided against Apple, as were later appeals. Apple’s actions were criticized by some in the software community, including the Free Software Foundation (FSF), who felt Apple was trying to monopolize on GUIs in general, and boycotted GNU software for the Macintosh platform for seven years.[37][38]

With the new Motorola 68030 processor came the Macintosh IIx in 1988, which had benefited from internal improvements, including an on-board MMU.[39] It was followed in 1989 by a more compact version with fewer slots (the Macintosh IIcx)[40] and a version of the Mac SE powered by the 16 MHz 68030, the Macintosh SE/30.[41] Later that year, the Macintosh IIci, running at 25 MHz, was the first Mac to be “32-bit clean,” allowing it to natively support more than 8 MB of RAM,[42] unlike its predecessors, which had “32-bit dirty” ROMs (8 of the 32 bits available for addressing were used for OS-level flags). System 7 was the first Macintosh operating system to support 32-bit addressing.[43] Apple also introduced the Macintosh Portable, a 16 MHz 68000 machine with an active matrix flat panel display that was backlit on some models.[44] The following year the Macintosh IIfx, starting at US$9,900, was unveiled. Apart from its fast 40 MHz 68030 processor, it had significant internal architectural improvements, including faster memory and two Apple II-era CPUs dedicated to I/O processing.[45]

1990 to 1998: Growth and decline

Microsoft Windows 3.0, which began to approach the Macintosh operating system in both performance and feature set, was released in May 1990 and was a usable, less expensive alternative to the Macintosh platform. Apple's response was to introduce a range of relatively inexpensive Macs in October 1990. The Macintosh Classic, essentially a less expensive version of the Macintosh Plus, was the least expensive Mac until early 2001.[46] The 68020-powered Macintosh LC, in its distinctive “pizza box” case, offered color graphics and was accompanied by a new, low-cost 512 × 384 pixel monitor.[47] The Macintosh IIsi was essentially a 20 MHz IIci with only one expansion slot.[48] All three machines sold well,[49] although Apple’s profit margin was considerably lower than on earlier machines.[46]

Apple's microchips improved. The Macintosh Classic II[50] and Macintosh LC II, which used a 16 MHz 68030 CPU,[51] were joined in 1991 by the Macintosh Quadra 700[52] and 900,[53] the first Macs to employ the faster Motorola 68040 processor. In 1994, Apple abandoned Motorola CPUs for the RISC PowerPC architecture developed by the AIM alliance of Apple Computer, IBM, and Motorola.[54] The Power Macintosh line, the first to use the new chips, proved to be highly successful, with over a million PowerPC units sold in nine months.[55]

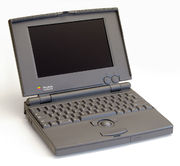

Apple replaced the Macintosh Portable in 1991 with the first of the PowerBook line: the PowerBook 100, a miniaturized Portable; the 16 MHz 68030 PowerBook 140; and the 25 MHz 68030 PowerBook 170.[56] They were the first portable computers with the keyboard behind a palm rest, and with a built-in pointing device (a trackball) in front of the keyboard.[57] The 1993 PowerBook 165c was Apple's first portable computer to feature a color screen, specifically 8-bits with 640 x 400 pixels.[58] The second-generation of PowerBooks, the 500 series, introduced the trackpad in 1994.

As for Mac OS, System 7 was a 32-bit rewrite that introduced virtual memory, and improved the handling of color graphics, memory addressing, networking, and co-operative multitasking. Also during this time, the Macintosh began to shed the "Snow White" design language, along with the expensive consulting fees they were paying to Frogdesign, in favor of bringing the work in-house by establishing the Apple Industrial Design Group. They became responsible for to crafting a new look to go with the new operating system and all other Apple products.[59]

Despite these technical and commercial successes, Microsoft and Intel began to rapidly lower Apple's market share with the Windows 95 operating system and Pentium processors respectively. These significantly enhanced the multimedia capability and performance of IBM PC compatible computers, and brought Windows still closer to the Mac GUI. Furthermore, Apple had created too many similar models that confused potential buyers. At one point Apple offered Classics, LCs, IIs, Quadras, Performas, and Centrises.[60] These models competed against the Macintosh clones, hardware manufactured by third-parties that ran Apple's System 7. This succeeded in increasing the Macintosh's market share somewhat and provided cheaper hardware for consumers, but hurt Apple financially.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he ordered that the OS that had been previewed as version 7.7 be branded Mac OS 8 (in place of the never-to-appear Copland OS). Since Apple had licensed only System 7 to third-parties, this move effectively ended the clone line. The decision caused significant financial losses for companies like Motorola, who produced the StarMax, Umax, who produced the SuperMac,[61] and Power Computing Corporation, who offered several lines Mac clones, including PowerWave, PowerTower, and PowerTower Pro.[62] These companies had invested substantial resources in creating their own Mac-compatible hardware.[63]

1998 to 2005: New beginnings

In 1998, a year after Steve Jobs had returned to the company, Apple introduced an all-in-one Macintosh called the iMac. Its translucent plastic case, originally Bondi blue and later many other colors, is considered an industrial design hallmark of the late 1990s. The iMac did away with most of Apple's standard (and usually proprietary) connections, such as SCSI and ADB, in favor of two USB ports. It also had no internal floppy disk drive and instead used compact discs for removable storage.[3][65] It proved to be phenomenally successful, with 800,000 units sold in 139 days,[66] making the company an annual profit of US$309 million—Apple's first profitable year since Michael Spindler took over as CEO in 1995.[67] The "blue and white" aesthetic was applied to the Power Macintosh, and then to a new product: the iBook. Introduced in July 1999, the iBook was Apple's first consumer-level laptop computer. More than 140,000 pre-orders were placed before it started shipping in September,[68] and by October it was as much a sales hit as the iMac.[69] Apple continued to add new products to their lineup, such as the Power Mac G4 Cube,[70] the eMac for the education market and PowerBook G4 laptop for professionals. The original iMac used a G3 processor, but the upgrades to G4 and then to G5 chips were accompanied by a new design, dropping the array of colors in favor of white plastic. Current iMacs use aluminum enclosures. On January 11, 2005, Apple announced the release of the Mac Mini priced at US$499,[71] the least expensive Mac to date.[72]

Mac OS continued to evolve up to version 9.2.2, including retrofits such as the addition of a nanokernel and support for Multiprocessing Services 2.0 in Mac OS 8.6.[73] Ultimately its dated architecture made replacement necessary. As such, Apple introduced Mac OS X, a fully overhauled Unix-based successor to Mac OS 9, using Darwin, XNU, and Mach as foundations, and based on NEXTSTEP. Mac OS X was not released to the public until September 2000, as the Mac OS X Public Beta, with an Aqua interface. At US$29.99, it allowed adventurous Mac users to sample Apple’s new operating system and provide feedback for the actual release.[74] The initial release of Mac OS X, 10.0 (nicknamed Cheetah), was released on March 24, 2001. Older Mac OS applications could still run under early Mac OS X versions, using an environment called Classic. Subsequent releases of Mac OS X were 10.1 "Puma" (September 25, 2001), 10.2 "Jaguar" (August 24, 2002), 10.3 "Panther" (October 24, 2003), 10.4 "Tiger" (April 29, 2005), 10.5 "Leopard" (October 26, 2007), and 10.6 "Snow Leopard" (August 28, 2009).[75] Leopard and Snow Leopard each received certification as a Unix implementation by The Open Group.[76][77]

2006 onward: Intel era

Apple discontinued the use of PowerPC microprocessors in 2006. At WWDC 2005, Steve Jobs revealed this transition and also noted that Mac OS X was in development to run both on Intel and PowerPC architecture from the very beginning.[79] All new Macs now use x86 processors made by Intel, and some Macs were given new names to signify the switch.[80] Intel-based Macs can run pre-existing software developed for PowerPC using an emulator called Rosetta,[81] although at noticeably slower speeds than native programs, and the Classic environment is unavailable. With the release of Intel-based Mac computers, the potential to natively run Windows-based operating systems on Apple hardware without the need for emulation software such as Virtual PC was introduced. In March 2006, a group of hackers announced that they were able to run Windows XP on an Intel-based Mac. The group released their software as open source and has posted it for download on their website.[82] On April 5, 2006 Apple announced the public beta availability of their own Boot Camp software which allows owners of Intel-based Macs to install Windows XP on their machines; later versions added support for Windows Vista. Boot Camp became a standard feature in Mac OS X 10.5, while support for Classic was dropped from PowerPC Macs.[83][84]

Apple's recent industrial design has shifted to favor aluminum and glass, which is billed as environmentally friendly.[85] The iMac and MacBook Pro lines use aluminum enclosures, and both are now made of a single unibody.[86][87] Chief designer Jonathan Ive continues to guide products towards a minimalist and simple feel,[88][89] including the elimination of replaceable batteries in notebooks.[90] Multi-touch gestures from the iPhone's interface have been applied to the Mac line in the form of touch pads on notebooks and the Magic Mouse for desktops.

In recent years, Apple has seen a significant boost in sales of Macs. Many claim that this is due, in part, to the success of the iPod, a halo effect whereby satisfied iPod owners purchase more Apple equipment. The inclusion of the Intel chips is also a factor. From 2001 to 2008, Mac sales increased continuously on an annual basis. Apple reported sales of 3.36 million Macs during the 2009 holiday season.[91]

Timeline of Macintosh models

Product line

| Compact | Consumer | Professional | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desktop | Mac mini Entry-level; ships without keyboard, mouse, or monitor; uses Intel Core 2 Duo processors |

iMac All-in-one; available in 21.5" and 27" screen sizes; uses Intel Core 2 Duo, Intel Core i5, or Intel Core i7 processors |

Mac Pro Workstation desktop; highly customizable; uses up to two Intel Xeon 5500 "Gainestown" or Xeon 3500 "Bloomfield" quad-core processors |

|||

| Portable (MacBook) |

MacBook Air 13.3" ultraportable with aluminum casing; uses Intel Core 2 Duo processors |

MacBook 13.3" laptop with white polycarbonate casing; uses Intel Core 2 Duo processors |

MacBook Pro 13.3", 15.4" or 17" models with aluminum casing; uses Intel Core 2 Duo, Intel Core i5, or Intel Core i7 processors |

|||

| Server | Mac mini An additional Mac mini configuration without an internal optical drive. Ships with Mac OS X Server installed and two internal 500 GB hard drives for a total of 1 TB of capacity. |

Mac Pro An additional Mac Pro server configuration. Ships with Mac OS X Server installed. 4×2=8 GiB memory, and 2×1=2 TB hard-disk drive space. |

Xserve 1U rack-mount; uses dual quad-core Intel Xeon processors for up to 8 cores |

|||

Hardware and software

Hardware

Apple directly sub-contracts hardware production to Asian original equipment manufacturers such as Asus, maintaining a high degree of control over the end product. By contrast, most other companies (including Microsoft) create software that can be run on hardware produced by a variety of third-parties, like Dell, HP/Compaq, and Lenovo. Consequently, the Macintosh buyer has comparably fewer options.

The current Mac product family uses Intel x86-64 processors. Apple introduced an emulator during the transition from PowerPC chips (called Rosetta), much as it did during the transition from Motorola 68000 architecture a decade earlier. All current Mac models ship with at least 2 GB RAM as standard. Current Mac computers use ATI Radeon or nVidia GeForce graphics cards. All current Macs (except for the MacBook Air) ship with an optical media drive that includes a dual-function DVD and CD burner, called the SuperDrive. Macs include two standard data transfer ports: USB and FireWire (except for the MacBook Air and MacBook, which do not include FireWire). USB was introduced in the 1998 iMac G3 and is ubiquitous today,[3] while FireWire is mainly reserved for high-performance devices such as hard drives or video cameras. Starting with a new iMac G5 released in October 2005, Apple started to include built-in iSight cameras to appropriate models, and a media center interface called Front Row that can be operated by an Apple Remote or keyboard for accessing media stored on the computer.[92]

Apple was initially reluctant to embrace mice with multiple buttons and scroll wheels. Macs did not natively support multiple buttons, even from third parties, until Mac OS X arrived in 2001.[93] Apple continued to offer only single button mice, with wired and Bluetooth wireless versions, until August 2005, when it introduced the Mighty Mouse. While it looked like a traditional one-button mouse, it actually had four buttons and a scroll ball, capable of independent x- and y-axis movement.[94] A Bluetooth version followed in July 2006.[95] In October 2009, Apple introduced the Magic Mouse which uses multi-touch gesture recognition similar to the iPhone instead of a physical scroll wheel or ball.[96] It is available only in Bluetooth, and the Mighty Mouse (re-branded as "Apple Mouse") is available with a cord.

Software

The original Macintosh was the first successful personal computer to use a graphical user interface devoid of a command line. It used a desktop metaphor, depicting real-world objects like documents and a trashcan as icons onscreen. The System software introduced in 1984 with the first Macintosh and renamed Mac OS in 1997, continued to evolve until version 9.2.2. In 2001, Apple introduced Mac OS X, based on Darwin and NEXTSTEP; its new features included the Dock and the Aqua user interface. During the transition, Apple included an emulator known as Classic allowing users to run Mac OS 9 applications under Mac OS X, version 10.4 and earlier on PowerPC machines. The most recent version is Mac OS X v10.6 "Snow Leopard." In addition to Snow Leopard, all new Macs are bundled with assorted Apple-produced applications, including iLife, the Safari web browser and the iTunes media player.

Mac OS X enjoys a near-absence of the types of malware and spyware that affect Microsoft Windows users.[97][98][99] Mac OS X has a smaller usage share compared to Microsoft Windows (roughly 5% and 92%, respectively),[100] but it also has secure UNIX roots. Worms as well as potential vulnerabilities were noted in February 2006, which led some industry analysts and anti-virus companies to issue warnings that Apple's Mac OS X is not immune to malware.[101] Apple routinely issues security updates for its software.[102]

Originally, the hardware architecture was so closely tied to the Mac OS operating system that it was impossible to boot an alternative operating system. The most common workaround, used even by Apple for A/UX, was to boot into Mac OS and then to hand over control to a program that took over the system and acted as a boot loader. This technique was no longer necessary with the introduction of Open Firmware-based PCI Macs, though it was formerly used for convenience on many Old World ROM systems due to bugs in the firmware implementation. Now, Mac hardware boots directly from Open Firmware or EFI, and Macs are no longer limited to running just the Mac OS X.

Following the release of the Intel-based Mac, third-party platform virtualization software such as Parallels Desktop, VMware Fusion, and VirtualBox began to emerge. These programs allow users to run Microsoft Windows or previously Windows-only software on Macs at near native speed. Apple also released Boot Camp and Mac-specific Windows drivers, which help users to install Windows XP or Vista and natively dual boot between Mac OS X and Windows. Though not condoned by Apple, it is possible to run the Linux operating system using Boot camp or other virtualization workarounds.[103][104][105]

Because Mac OS X is a UNIX like system, borrowing heavily from FreeBSD, many applications written for Linux or BSD run on Mac OS X, often using X11. Apple's less-common operating system means that a much smaller range of third-party software is available, but many popular applications such as Microsoft Office and Firefox are cross-platform and run natively.

Advertising

Macintosh advertisements have usually attacked the established market leader, directly or indirectly. They tend to portray the Mac as an alternative to overly complex or unreliable PCs. Apple hyped the introduction of the original Mac with their 1984 commercial, which aired during the Super Bowl.[106] It was supplemented by a number of printed pamphlets and other TV ads demonstrating the new interface and emphasizing the mouse. Many more brochures for new models like the Macintosh Plus and the Performa followed. In the 1990s, Apple started the “What's on your PowerBook?” campaign, with print ads and television commercials featuring celebrities describing how the PowerBook helps them in their businesses and everyday lives. In 1995, Apple responded to the introduction of Windows 95 with several print ads and a television commercial demonstrating its disadvantages and lack of innovation. In 1997 the Think Different campaign introduced Apple’s new slogan, and in 2002 the Switch campaign followed. The most recent advertising strategy by Apple is the Get a Mac campaign, with North American, UK and Japanese variants.[107][108]

Today, Apple introduces new products at “special events” at the Apple Town Hall auditorium, and keynotes at the Apple Worldwide Developers Conference, and (formerly) trade shows like the Apple Expo and the MacWorld Expo. The events typically draw a large gathering of media representatives and spectators, and are preceded by speculation about possible new products. In the past, special events have been used to unveil its desktop and notebook computers such as the iMac and MacBook, and other consumer electronic devices like the iPod, Apple TV, and iPhone, as well as provide updates on sales and market share statistics. Apple has begun to focus its advertising on its retail stores instead of these trade shows; the last MacWorld keynote was in 2009.[109]

Since the introduction of the Macintosh, Apple has struggled to gain a significant share of the personal computer market. At first, the Macintosh 128K suffered from a dearth of available software compared to IBM's PC, resulting in disappointing sales in 1984 and 1985. It took 74 days for 50,000 units to sell.[110] Market share is measured by browser hits, sales and installed base. If using the browser metric, Mac market share has increased substantially in 2007.[111] If measuring market share by installed base, there were more than 20 million Mac users by 1997, compared to an installed base of around 340 million Windows PCs.[112][113] Statistics from late 2003 indicate that Apple had 2.06 percent of the desktop share in the United States, which had increased to 2.88 percent by Q4 2004.[114] As of October 2006, research firms IDC and Gartner reported that Apple's market share in the U.S. had increased to about 6 percent.[115] Figures from December 2006, showing a market share around 6 percent (IDC) and 6.1 percent (Gartner) are based on a more than 30 percent increase in unit sale from 2005 to 2006. The installed base of Mac computers is hard to determine, with numbers ranging from 5% (estimated in 2009)[116] to 16% (estimated in 2005).[117] Mac OS X’s share of the OS market increased from 7.31% in December 2007 to 9.63% in December 2008, which is a 32% increase in market share during 2008, compared to a 22% increase during 2007.

Whether the size of the Mac’s market share and installed base is actually relevant, and to whom, is a hotly debated issue. Industry pundits have often called attention to the Mac’s relatively small market share to predict Apple's impending doom, particularly in the early and mid 1990s when the company’s future seemed bleakest. Others argue that market share is the wrong way to judge the Mac’s success. Apple has positioned the Mac as a higher-end personal computer, and so it may be misleading to compare it to a low-budget PC.[118] Because the overall market for personal computers has grown rapidly, the Mac’s increasing sales numbers are effectively swallowed by the industry’s numbers as a whole. Apple’s small market share, then, gives the false impression that fewer people are using Macs than did (for example) ten years ago.[119] Others try to de-emphasize market share, citing that it is rarely brought up in other industries.[120] Regardless of the Mac’s market share, Apple has remained profitable since Steve Jobs’ return and the company’s subsequent reorganization.[121] Notably, a report published in the first quarter of 2008 found that Apple had a 14% market share in the personal computer market in the US, including 66% of all computers over $1,000.[122] Market research indicates that Apple draws its customer base from a higher-income demographic than the mainstream personal computer market.[123]

See also

- Apple Inc. litigation

- Apple rumors community

- History of computing hardware (1960s-present)

- List of Macintosh models by case type

- List of Macintosh models grouped by CPU type

- List of Macintosh software

- List of Macintosh software published by Microsoft

- Mac gaming

- Reality distortion field

Notes

- ↑ "Define Macintosh". Dictionary.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/macintosh. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ↑ Polsson, Ken (2009-07-29). "Chronology of Apple Computer Personal Computers". http://www.islandnet.com/~kpolsson/applehis/appl1984.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-27. See May 3, 1984.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Edwards, Benj (2008-08-15). "Eight ways the iMac changed computing". Macworld. http://www.macworld.com/article/135017/2008/08/imacanniversary.html. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ↑ Raskin, Jef (1996). "Recollections of the Macintosh project". Articles from Jef Raskin about the history of the Macintosh.. http://mxmora.best.vwh.net/JefRaskin.html. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- ↑ Apple confidential 2.0: the definitive history of the world's most colorful company, Owen W. Linzmayer, ISBN 978-1-59327-010-0

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hertzfeld, Andy. "The father of the Macintosh". Folklore.org. http://www.folklore.org/StoryView.py?project=Macintosh&story=The_Father_of_The_Macintosh.txt&showcomments=1#comments. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Crow, George. "The Original Macintosh". Folklore.org. http://www.folklore.org/ProjectView.py?project=Macintosh&characters=George%20Crow. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Kottke, Dan. "The Original Macintosh". Folklore.org. http://www.folklore.org/ProjectView.py?project=Macintosh&characters=Dan%20Kottke. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Manock, Jerry. "The Original Macintosh". Folklore.org. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070929111006/http://folklore.org/ProjectView.py?project=Macintosh&characters=Jerry%20Manock. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Kawasaki, Guy (2009-01-26). "Macintosh 25th Anniversary Reunion: Where Did Time Go?". http://blog.guykawasaki.com/2009/01/twenty-five-yea.html#axzz0mQb8tIS0. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Hertzfeld, Andy. "Five different Macintoshes". Folklore.org. http://www.folklore.org/StoryView.py?story=Five_Different_Macs.txt. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Horn, Bruce. "On Xerox, Apple and Progress". Folklore.org. http://www.folklore.org/StoryView.py?project=Macintosh&story=On_Xerox,_Apple_and_Progress.txt. Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ↑ Tracy, Ed. "History of computer design: Snow White". Landsnail.com. http://www.landsnail.com/apple/local/design/design2.html. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Hertzfeld, Andy. "The End Of An Era". folklore.org. http://www.folklore.org/StoryView.py?project=Macintosh&story=The_End_Of_An_Era.txt.

- ↑ Spector, G (1985-09-24). "Apple's Jobs Starts New Firm, Targets Education Market". PCWeek: p. 109.

- ↑ "Apple Computer, Inc. Finalizes Acquisition of NeXT Software Inc.". Apple. 1997-02-07. http://web.archive.org/web/19990117075346/http://product.info.apple.com/pr/press.releases/1997/q2/970207.pr.rel.next.html. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "Apple Macintosh 18 Page Brochure". DigiBarn Computer Museum. http://www.digibarn.com/collections/ads/apple-mac/index.htm. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Linzmayer, Owen W. (2004). Apple Confidential 2.0. No Starch Press. pp. 113. ISBN 1-59327-010-0. http://www.owenink.com.

- ↑ Maney, Kevin (2004-01-28). "Apple's '1984' Super Bowl commercial still stands as watershed event". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/tech/columnist/kevinmaney/2004-01-28-maney_x.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ↑ Leopold, Todd (2006-02-03). "Why 2006 isn't like '1984'". CNN. http://edition.cnn.com/2006/SHOWBIZ/02/02/eye.ent.commercials/. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ↑ Cellini, Adelia (January 2004). "The Story Behind Apple's '1984' TV commercial: Big Brother at 20". MacWorld 21.1, page 18. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb197/is_200401/ai_n5556112. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ↑ Long, Tony (2007-01-22). "Jan. 22, 1984: Dawn of the Mac". Wired. http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2007/01/72496. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ↑ Kahney, Leander (2004-01-06). "We're All Mac Users Now". Wired. http://www.wired.com/gadgets/mac/news/2004/01/61730. Retrieved 2010-04-11.

- ↑ Polsson, Ken. "Chronology of Apple Computer Personal Computers". http://www.islandnet.com/~kpolsson/applehis/appl1984.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

- ↑ Beamer, Scott (1992-01-13). "For Lotus, third time's the charm". MacWEEK. http://www.accessmylibrary.com/article-1G1-11721498/lotus-third-time-charm.html. Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hormby, Thomas (2006-10-02). "Apple's Worst Business Decisions". OS News. http://www.osnews.com/story/16036/Apples-Worst-Business-Decisions/. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "1984 Newsweek Macintosh ads". GUIdebook, Newsweek. http://www.guidebookgallery.org/ads/magazines/macos/macos10-newsweek. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ "Inflation Calculator". Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- ↑ Spring, Michael B. (1991). Electronic printing and publishing: the document processing revolution. CRC Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9780824785444. http://books.google.com/?id=_MV46vFUrI4C&pg=PA125&dq=Desktop+publishing+history+of&cd=5#v=onepage&q=Desktop%20publishing%20history%20of.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh 512K from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh Plus from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh II from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ "Apple Macintosh II". Old Computers On-line Museum. http://www.old-computers.com/museum/computer.asp?st=1&c=160. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ "Macintosh II Family: Fan Regulator Voids Warranty". Apple. 1992-07-02. http://docs.info.apple.com/article.html?artnum=4648&coll=ap. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh SE from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Hearm, Bob (2003). "A Brief History of ClarisWorks". MIT Project on Mathematics and Computation. http://www-swiss.ai.mit.edu/~bob/clarisworks.php. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ Free Software Foundation (1988-06-11). "Special Report: Apple's New Look and Feel". GNU's Bulletin 1 (5). http://www.gnu.org/bulletins/bull5.html#SEC9. Retrieved 2006-04-25.

- ↑ Free Software Foundation (1995-01). "End of Apple Boycott". GNU's Bulletin 1 (18). http://www.gnu.org/bulletins/bull18.html#SEC13. Retrieved 2006-04-25.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh IIx from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh IIcx from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh SE/30 from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh IIci from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Knight, Dan (2001-01). "32-bit Addressing on Older Macs". Low End Mac. http://lowendmac.com/trouble/32bit.shtml. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh Portable from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh IIfx from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Fisher, Lawrence M. (1990-10-15). Less-Costly Apple Line To Be Presented Today. The New York Times. Retrieved on January 16, 2008.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh LC from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh IIsi from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Fisher, Lawrence M. (1991-01-18). "I.B.M. Surprises Wall Street With Strong Quarterly Net; Apple Posts 20.6% Rise". The New York Times. Retrieved on 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh Classic II from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh LC II from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh Quadra 700 from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of Macintosh Quadra 900 from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Hormby, Thomas (2005-01-03). "Apple's Transition to PowerPC put in perspective". Kaomso. http://www.kaomso.com/FullStory.php?TheStory=78. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ Polsson, Ken (2007-12-16). "Chronology of Apple Computer Personal Computers". http://www.islandnet.com/~kpolsson/applehis/appl1994.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ Polsson, Ken. "Chronology of Apple Computer Personal Computers". http://www.islandnet.com/~kpolsson/applehis/appl1990.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

- ↑ Jade, Kasper (2007-02-16). "Apple to re-enter the sub-notebook market". AppleInsider. http://www.appleinsider.com/articles/07/02/16/apple_to_re_enter_the_sub_notebook_market.html. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ Technical specifications of PowerBook 165c from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Kunkel, Paul (October 1, 1997). AppleDesign: The work of the Apple Industrial Design Group. Rick English (photographs). New York City: Graphis Inc.. ISBN 1888001259.

- ↑ Apple Computer (1995-06-19). "Macintosh Centris, Quadra 660AV: Description (Discontinued)". http://docs.info.apple.com/article.html?artnum=12707&coll=ap. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ EveryMac.com (2009-10-27). "Umax Mac Clones (MacOS-Compatible Systems)". http://www.everymac.com/systems/umax/index-umax-supermac-mac-clones.html. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ EveryMac.com (2009-10-27). "PowerComputing Mac Clones (MacOS-Compatible Systems)". http://www.everymac.com/systems/powercc/index-power-computing-mac-clones.html. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ Knight, Dan (2007-08-30). "1997: Apple Squeezes Mac Clones Out of the Market". Low End Mac. http://lowendmac.com/musings/mm07/0830.html. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ Engst, Adam (2009-01-23). "The six worst Apple products of all time". Macworld. http://www.macworld.com/article/138404/2009/01/macat25_worstproducts.html. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Technical specifications of iMac G3 from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ "800,000 iMacs Sold in First 139 Days". Apple. 1999-01-05. http://www.apple.com/ca/press/1999/01/iMac_Sales.html. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ Markoff, John (1998-10-15). "COMPANY REPORTS; Apple's First Annual Profit Since 1995". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CE6D8123AF936A25753C1A96E958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ "Apple Averages Three Thousand iBooks Per Day In Pre-orders!". The Mac Observer. 1999-08-31. http://www.macobserver.com/news/99/august/990831/140000ibooks.html. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "PC Data Ranks iBook Number One Portable in U.S.". Apple. 2000-01-25. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2000/jan/25ibook.html. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ "About the Macintosh Cube" (PDF). Apple. 2000. http://manuals.info.apple.com/en/PowerMacG4_CubeAbout.PDF. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Markoff, John; Hansell, Saul (2005-01-12). "Apple Changes Course With Low-Priced Mac." New York Times. Retrieved on 2006-01-16.

- ↑ Apple unveils low-cost 'Mac mini'. BBC News. 2005-01-11. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/4162009.stm. Retrieved 28 April 2010

- ↑ "Apple Developer Connection – Overview of the PowerPC System Software". Apple. http://developer.apple.com/documentation/mac/PPCSoftware/PPCSoftware-12.html#HEADING12-0. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- ↑ Biersdorfer, J.D. (2000-09-14). "Apple Breaks The Mold." New York Times'.' Retrieved on 2008-01-16.

- ↑ "Apple Unveils Mac OS X Snow Leopard". Apple. 2009-06-08. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2009/06/08macosx.html. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ "Mac OS X Leopard Achieves UNIX 03 Product Standard Certification". The Open Group. 2007-11-19. http://www.opengroup.org/comm/press/19-2-nov07.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ↑ "Mac OS X Snow Leopard Achieves UNIX 03 Product Standard Certification". The Open Group. 2009-10-22. http://www.opengroup.org/openbrand/register/brand3581.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ↑ Technical specifications of MacBook Pro from Apple's knowledge base and from EveryMac.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ "Apple to Use Intel Microprocessors Beginning in 2006". Apple. 2005-06-06. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2005/jun/06intel.html. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Michaels, Philip (2010-01-02). "Apple's most significant products of the decade". Macworld. http://www.macworld.com/article/145380/2010/01/10significantapplemoves.html. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ "WWDC 2005 Keynote Live Update". Macworld. 2005-06-06. http://www.macworld.com/article/45157/2005/06/liveupdate.html. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ "Hackers get Windows XP to run on a Mac". MSNBC (AP). 2006-03-17. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/11885495/. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ "Boot Camp". Apple. http://www.apple.com/support/bootcamp/. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Jim (2006-03-05). "New Apple software lets Intel Macs boot Windows". Macworld. http://www.macworld.com/article/50204/2006/04/bootcamp.html. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ "The story behind Apple's environmental footprint.". Apple. http://www.apple.com/environment/complete-lifecycle/#recycling. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ "New MacBook Family Redefines Notebook Design". Apple. 2008-10-14. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2008/10/14macbook.html. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ Lam, Brian (2009-10-20). "Apple iMac Hands On". Gizmodo. http://gizmodo.com/5385841/apple-imac-hands-on. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ↑ Kahney, Leander (2003-06-25). "Design According to Ive". Wired. http://www.wired.com/culture/design/news/2003/06/59381?currentPage=all. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ Nosowitz, Dan (2009-11-07). "Watch Jonathan Ive's Segment in Objectified". Gizmodo. http://gizmodo.com/5399420/watch-jonathan-ives-segment-in-objectified. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ "Apple Updates MacBook Pro Family with New Models & Innovative Built-in Battery for Up to 40% Longer Battery Life". Apple. 2009-06-08. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2009/06/08mbp.html. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ "Apple Reports First Quarter Results". Apple. 2009-01-25. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2010/01/25results.html.

- ↑ "Apple Introduces the New iMac G5". Apple. 2005-10-12. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2005/oct/12imac.html. Retrieved 2006-07-12.

- ↑ "Eek! A Two-Button Mac Mouse?". Wired. 2000-10-30. http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2000/10/39773. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ "Apple Introduces Mighty Mouse". Apple. 2005-08-02. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2005/aug/02mightymouse.html. Retrieved 2006-07-12.

- ↑ "Apple Debuts Wireless Mighty Mouse". Apple. 2006-07-25. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2006/jul/25mightymouse.html. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ↑ "Apple Introduces Magic Mouse—The World’s First Multi-Touch Mouse". Apple. 2009-10-20. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2009/10/20magicmouse.html. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ Welch, John (2007-01-06). "Review: Mac OS X Shines In Comparison With Windows Vista". Information Week. http://www.informationweek.com/news/showArticle.jhtml?articleID=196800670&pgno=4&queryText=. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- ↑ Granneman, Scott (2003-10-06). "Linux vs. Windows Viruses". The Register. http://www.theregister.co.uk/2003/10/06/linux_vs_windows_viruses/. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- ↑ Gruber, John (2004-06-04). "Broken Windows". Daring Fireball. http://daringfireball.net/2004/06/broken_windows. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ "Operating System Market Share". September 2009. http://marketshare.hitslink.com/operating-system-market-share.aspx?qprid=8. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ↑ Roberts, Paul (2006-02-21). "New Safari Flaw, Worms Turn Spotlight on Apple Security". eWeek. http://www.eweek.com/article2/0,1895,1929342,00.asp. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Apple security updates". Apple. 2009-01-21. http://support.apple.com/kb/HT1222. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ↑ Scott, Chris. "How to install Linux on an Intel Mac with Boot Camp". Helium Inc. http://www.helium.com/items/421906-how-to-install-linux-on-an-intel-mac-with-boot-camp. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ Lucas, Paul (2005-06-04). "Paul J. Lucas's Mac Mini running Linux". http://homepage.mac.com/pauljlucas/personal/macmini/index.html. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ Hoover, Lisa (2008-04-11). "Virtualization Makes Running Linux a Snap". http://ostatic.com/blog/virtualization-makes-running-linux-a-snap. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- ↑ Pogue, David; Joseph Schorr (1993). Macworld Macintosh SECRETS. San Mateo: IDG Books Worldwide, Inc.. p. 251. ISBN 1-56884-025-X.

- ↑ "Get a Mac advertisements". Apple. http://www.apple.com/uk/getamac/. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ↑ "Get a Mac". Apple. http://www.apple.com/jp/getamac/. Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ↑ "Apple Announces Its Last Year at Macworld". Apple. 2008-12-16. http://www.apple.com/pr/library/2008/12/16macworld.html. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ↑ Polsson, Ken (2009-07-29). "Chronology of Apple Computer Personal Computers". http://www.islandnet.com/~kpolsson/applehis/appl1984.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-27. See April 7, 1984.

- ↑ "Trends in Mac market share". Ars Technica. 2009-04-05. http://arstechnica.com/journals/apple.ars/2007/04/05/trends-in-mac-market-share. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ↑ "Apple Developer News, No. 87". Apple Computer. 1997-12-19. http://developer.apple.com/adcnews/pastissues/devnews121997.html#stats. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ "Nearly 600 Million Computers-in-Use in Year 2000". Computer Industry Almanac Inc. 1998-11-03. http://www.c-i-a.com/pr1198.htm. Retrieved 2006-06-01.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Jim (2005-04-20). "Apple desktop market share on the rise; will the Mac mini, iPod help?". Macworld. http://www.macworld.com/news/2005/03/20/marketshare/index.php. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Jim (2006-10-19). "Apple's Mac market share tops 5% with over 30% growth". Macworld. http://www.macworld.com/news/2006/10/19/marketshare/index.php. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

- ↑ "Operating System Market Share". Hitslink. July 2009. http://marketshare.hitslink.com/operating-system-market-share.aspx?qprid=8. Retrieved 2009-08-27.

- ↑ MacDailyNews (2005-06-15). "16% of computer users are unaffected by viruses, malware because they use Apple Macs". http://macdailynews.com/index.php/weblog/comments/5933/. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Gruber, John (2003-07-23). "Market Share". Daring Fireball. http://daringfireball.net/2003/07/market_share. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Brockmeier, Joe (2003-05-13). "What Will It Take To Put Apple Back on Top?". NewsFactor Magazine online. http://www.newsfactor.com/perl/story/21499.html. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Toporek, Chuck (2001-08-22). "Apple, Market Share, and Who Cares?". O'Reilly macdevcenter.com. http://www.oreillynet.com/mac/blog/2001/08/apple_market_share_and_who_car.html. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Spero, Ricky (2004-07-14). "Apple Posts Profit of $61 million; Revenue Jumps 30%". The Mac Observer. http://www.macobserver.com/stockwatch/2004/07/14.1.shtml. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- ↑ Wilcox, Joe. "Macs Defy Windows' Gravity". Apple Watch. http://blogs.eweek.com/applewatch/content/channel/macs_defy_windows-gravity.html. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ Fried, Ian (July 12, 2002). "Are Mac users smarter?". news.com. http://news.com.com/2100-1040-943519.html. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

References

- Apple & Raskin, Jef (1992). Macintosh Human Interface Guidelines. Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 0-201-62216-5.

- Apple. "Press release Library". http://www.apple.com/pr/library/. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

- Deutschman, Alan (2001). The Second Coming of Steve Jobs. Broadway. ISBN 0-7679-0433-8.

- Hertzfeld, Andy. "folklore.org: Macintosh stories". http://folklore.org/index.py. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- Hertzfeld, Andy (2004). Revolution in the Valley. O'Reilly Books. ISBN 0-596-00719-1.

- Kahney, Leander (2004). The Cult of Mac. No Starch Press. ISBN 1-886411-83-2.

- Kawasaki, Guy (1989). The Macintosh Way. Scott Foresman Trade. ISBN 0-673-46175-0.

- Kelby, Scott (2002). Macintosh... The Naked Truth. New Riders Press. ISBN 0-7357-1284-0.

- Knight, Dan (2005). "Macintosh History: 1984". http://lowendmac.com/history/1984dk.shtml. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- Levy, Steven (2000). Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-029177-6.

- Linzmayer, Owen (2004). Apple Confidential 2.0. No Starch Press. ISBN 1-59327-010-0.

- Page, Ian (2007). "MacTracker Macintosh model database 4.3.1". http://www.mactracker.ca/. Retrieved 2007-11-31.

- Sanford, Glen (2006). "Apple History". http://www.apple-history.com/. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

- Singh, Amit (2005). "A History of Apple's Operating Systems". http://www.kernelthread.com/mac/oshistory/. Retrieved 2006-04-24.

External links

- Making the Macintosh: Technology and Culture in Silicon Valley

- Welcome to MacIntosh (Full Film)

- MacHEADs (Full Film)

- Apple Confidential 20

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||